Beyond Ecosystem: Placemaking as the new starting point

Entrepreneurship and innovation ecosystems hold the promise of opportunities for everyone. To the credit of leaders supporting this work, the promise is achieved around the world through mobilising talent, focusing capital, developing policy, and providing incubation and founder support. And yet, there is an increasing tension in the inherent nature of these ecosystems to embed systemic inequalities, which become counterproductive, inhibiting innovation and reducing opportunities for underrepresented communities.

I have grappled with this tension over the past few years. In 2016, I was the inaugural manager of an Australian innovation hub in Ipswich, Queensland. As a local government-owned hub, I believed in the promise to provide pathways to entrepreneurship for everyone and leverage the hub to address local social challenges. And yet I struggled with what I saw as a disconnect between the expectations for reporting on impact indicators of high-technology jobs and new startups, and what I was seeing and hearing from practical community needs. Initiatives to create partnerships with public schools, provide experiences and support for community members with disabilities, or general community building stretched diminishing budgets targeted at economic diversification.

At the end of my PhD, which explored the enabling and inhibiting contributions of innovation hubs, I considered that we might need a new 'species' in the innovation ecosystem to support what was missing in both community needs and coordination in 'the space between' institutions and programs. The collective impact framework and associated backbone organisations seemed likely candidates for this work. I worked on a few community implementations, both of my own design and through the MIT Regional Entrepreneurship Acceleration Program (REAP) framework.

While promising on paper, it felt as though programs were inflicting ecosystems on communities. Where there was progress, frameworks seemed to stretch into areas not directly related to the program's definition of entrepreneurship. I was reminded of a quote I read in a journal article through my studies:

Most policy initiatives that would promote valuable entrepreneurship would not be recognisable as such. (2016, Acs et al, Public policy to promote entrepreneurship: a call to arms)

This statement reflected what I saw on the ground, where programs labelled as 'community development' or 'social services' might result in more entrepreneurs than yet another accelerator designed for those who already had access to support systems. I started to think we might need a new starting point.

This backstory provides a personal context to our recent presentation at the 2025 Global Entrepreneurship Congress (GEC) in Indianapolis, Indiana. The rest of this post provides an overview of the presentation, my personal reflections, and an invitation for others to continue and expand the conversation.

A big note of gratitude to the GEN organising team for not only providing the platform for us to present our provocation but also providing the innovative, rapid AI-driven review of each presentation on the GEC website. You can read the summary and watch the full presentation here: From Entrepreneurs to Communities: Rethinking Ecosystems Through Placemaking.

For additional reference, I am the founder and Chair of the Global Entrepreneurship Network Australia (GEN AU), which supported the hosting of the 2023 GEC in Melbourne and where we received the GEN Research Champion Award. I am also a Research Fellow with the University of Southern Queensland and co-founder with Kerry Grace of the place-based program Ready Communities.

Three starting propositions

The panel members included leaders from Kempsey, NSW, who participated in Ready Macleay as the first Ready Communities program in 2024. Jo-Anne Kelly is the Partnership Lead in the local backbone program out of the federal Department of Social Services' Stronger Places, Stronger People program. Jesse Poole is a Priest in the Anglican Diocese of Grafton for the Anglican Church of Australia.

Our panel began with a brief presentation to provide context for our conversation. In the first of three starting propositions, I highlighted findings from the predominance of research into inequality and innovation that highlights the extent to which innovation induces innovation. The same research also describes the extent to which inequality then hampers innovation, creating a downward cycle. Most would agree that innovation and entrepreneurship have improved overall living conditions, while also introducing new challenges from centralised wealth and increasingly marginalised communities based on geography and demographics.

The second proposition is that ecosystems reinforce inequality by providing opportunities to those who already have access. The ecosystem is defined by its preceding words, be it 'innovation' ecosystem, 'startup' ecosystem, or 'business' ecosystem. These can be adapted for special interest under a broad banner of inclusive ecosystems, for example, the Indigenous entrepreneur ecosystem or the female entrepreneur ecosystem.

These conditional modifications come with a cost and act as a regulation or slowing of resources in their natural tendency towards a path of least resistance. These regulations can be social, such as the Boulder thesis of 'give first' or a collective agreement in a community to focus on the disadvantaged. Regulations can also come from the government, such as innovation policies that mandate spending to address underrepresented communities. This creates a conflict point at the nexus of innovation and entrepreneurship's capacity for speed, disruption, and self-interest and the regulatory inhibitor.

The challenge is compounded when considering that characteristics of underrepresentation stack, increasing complexity and cost. A mature-aged female Indigenous entrepreneur who is a single parent in a remote community will have less access than a young, single, white male in a capital city. Depending on the community, support systems are expected to extend beyond an entrepreneur program into a local hub. They may incorporate programs more recognisable under community neighbourhood centres and family support infrastructure.

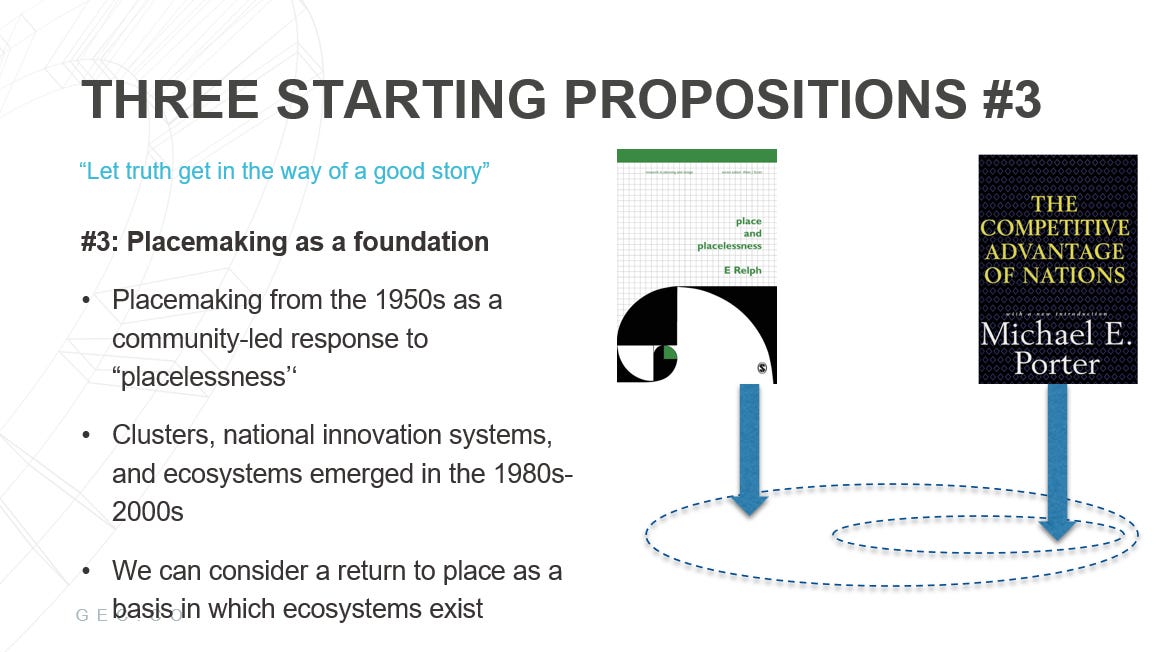

Instead of considering how we might adapt our notion of entrepreneur ecosystems, the previous discussion leads us to a third proposition: how we might consider placemaking and place-based development as a new starting point. We can mitigate criticism of following fads or being subject to pendulum swings of popular policy by placing the discussion in a historical context.

The interconnected nature of economies was acknowledged in Fredrick List's 1841 dissertation The National System of Political Economy. Alfred Marshall is credited with inspiring the concept of clusters with his notion of the Industrial District in his 1895 work, Principles of Economics. The term "ecosystem" originated decades later in 1935 as a reference to ecological systems. General systems theory was described shortly after in the 1940s.

The 1950s and 1960s saw critiques of urban expansion policies and a sense of 'placelessness', leading to calls for more community-led and people-centric development. The inherent complexity of systems was described in the 1970s and 1980s with the formalisation of the complex adaptive systems concept. The 1980s and 1990s saw the development of models to describe regional innovation systems, clusters, business ecosystems, networked regions, and the eventual innovation ecosystems and entrepreneur ecosystems, which usually have geographic boundaries. The ecosystem concept gained traction in the early 2000s, with discussions focusing on the conditions for effectiveness, measurement methods, inclusion criteria, and comparative rankings.

This review is succinct to the point of being overly reductionist. However, it provides context to the challenge that the ecosystem concept is only a few decades old and should not be taken as a given. It also acknowledges that the concept of placemaking preceded ecosystems. Perhaps the growth mandate inherent in ecosystems risks supplanting interventions that consider what is best for everyone in the community.

I need to reinforce that the conversation is not "either/or" but "yes/and". There are many amazing leaders involved in innovation and entrepreneur ecosystems, passionate about systemic change for the most vulnerable. What I am proposing is that these conversations sit within a broader and legitimised framework of placemaking that seems to be emerging in the collective global narrative.

The rest of the presentation was based on this proposition: that ecosystems by design are unable to stretch far enough to consider the factors in community that might best support entrepreneurs. Instead of starting with the entrepreneur as the central focus point, we start with the position of place, within which entrepreneurship and innovation play a key role.

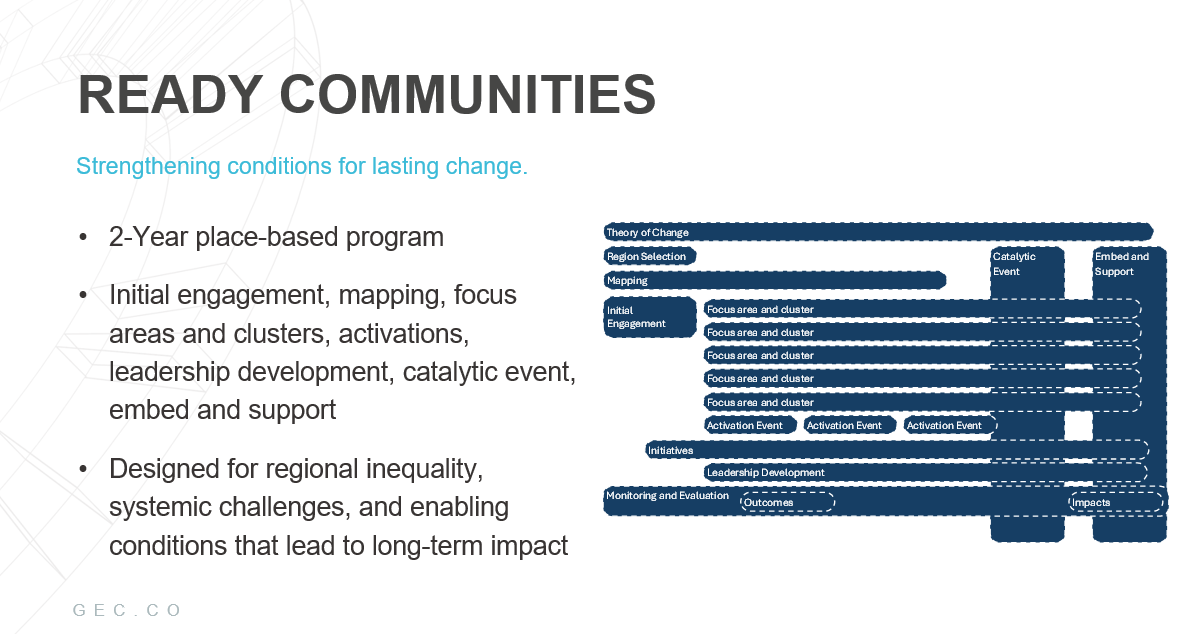

The remainder of the brief presentation provided a practical example and case study of the principles applied in practice using the Ready Communities program. This was not to say that Ready Communities was the only approach, but one example of other programs that provide scaffolding around community-led change.

In practical terms, a place-based program includes a series of elements, including: a Theory of Change and Program Logic, Region selection, Mapping, Initial engagement, Leadership identification and development, Focus area and cluster development, Activation events, Initiative identification and development, a catalytic event, monitoring and evaluation, and embedding and support. There are many variables, including duration, resourcing, and funding models. Programs also adapt to individual communities and can use different terms to describe what they do.

What is essential is to maintain the configuration of each element, rather than ad hoc delivery of individual components that are unable to effect systems-level change.

Mapping is an important part of the process. Rather than working backwards from an observed impact and attempting to identify the contributing factors, a bottom-up map through place-based change allows the change to be observed from connections, policy interventions, and funding over time. The graph below is the network map from mid-way through the Ready Macleay program.

Another critical distinction is a focus on outcomes, not impact. The diagram below shows the Ready Communities program logic of activities, outputs, outcomes, and impacts. While there is an impact framework with 128 indicators aligned to six dimensions of resilience, the focus is on the five enabling conditions of readiness.

The premise is that the impacts will result from an increase in the enabling conditions. Conversely, a focus on impacts such as jobs or investment can often stop when the focus policy or program is removed. Impacts may also be overinflated with programs that are designed to create jobs ignoring unintended consequences or creating short-term impacts to satisfy program requirements.

What we have seen in Kempsey is that participants at the intersection of the associated Social Impact in the Regions conference and Ready Macleay rated a higher increase across the five enabling conditions of clarity and understanding, connection and connectivity, capability and capacity, collaboration for purpose, and advocacy and promotion.

The five enabling conditions were developed in the lead-up to the 2023 Global Entrepreneurship Congress through over 30 workshops with over 500 leaders across Australia's broader impact and innovation ecosystem. The factors were refined through the Ready Macleay program and embedded into the evaluation framework.

In 2025, these enabling conditions were further operationalised into a Readiness Index with 50 indicators and 250 measures, plus a 360 community analysis. The results of this will be shared more in the 2025 Social Impact in the Regions conference in September 2025 in Grafton.

While the Ready Communities approach is grounded in academic underpinnings, decades of experience, and ongoing community feedback, it is the visible impact that tells the story. A white paper is in design and will be released in a few weeks with impact to date, including economic and social contribution of the Social Impact in the Regions conference and outcomes from the five focus areas of agriculture communities, creative industries, youth pathways, CBD activation, and housing and infrastructure.

A point that catalysed the impact of the program for me happened in Illinois at the conference. Two weeks before the conference, Kempsey and the wider region in New South Wales experienced flooding. Jo and Jesse both had pivotal roles in the community coordinating relief efforts, and there was consideration as to whether they attended the conference in the US. Their leadership teams released them to come based on the benefit of raising awareness, making connections, and bringing back resources and insights to their local community. These were realised with connections made with others who had first-hand experience at the intersection of entrepreneurship and disaster relief and bringing international contributions to the region in September.

But what really impacted me happened in a moment over a meal in town with Jo and Jesse on their phones coordinating with each other, relief resources, and their teams to coordinate response efforts in their community on the other side of the world. In that moment, we experienced the result of greater clarity of available resources, increased connectivity reducing friction, the capability and capacity of leaders and their organisations, the real-time functioning of collaboration for purpose, and shared advocacy for their region.

I will never say the outcome was entirely from the Ready Communities program. While the program introduced Jo and Jesse and facilitated shared experiences to build trust and relationships, there are many other programs and factors in the community. The people in the community do the work of working together. But we also acknowledge that the Ready Macleay program provided a framework or scaffolding around which the enabling conditions could be developed.

The conversation continued with Jo and Jesse, who reinforced the outcomes from the Ready Communities program and responded to questions, including:

Their personal reflections on the experience over the last year from their roles in a backbone organisation and a faith-based organisation

The work they do and how it correlates to innovation and entrepreneurship

Whether there is a dominant input on ecosystem-building efforts

How do you bring the long-term to nearby but do not fall into the trap of pursuing 'quick wins'

You can watch the full panel on the YouTube link here.

Ready Communities was created with Kerry Grace based on a recognition of a need and seeing the potential to contribute to change. While we believe in the approach, it is also constantly being refined based on what we are learning and feedback from others. We are grateful to those who have provided their wisdom to help design the program along the way.

This post is part of that process. It reflects a journey that is ongoing, in development, and informed by the collective community of people passionate about leading change in regional communities. As always, your comments and reflections are welcome as we learn and grow together.